If you’re having throat pain, difficulty swallowing, or are suffering from peptic ulcer disease, you might need esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD).

| Upper Endoscopy (EGD) FAQs |

| “Esophagogastroduodenoscopy” Upper endoscopy is also called EGD (EsophagoGastroDuodenoscopy) or gastroscopy. |

| This page will take you through the process of preparation for EGD at the Southwest Endoscopy Center. It contains useful information for “first timers” and for returning patients. Please call us if you have any questions or require any additional assistance. Our goal is to provide you with a safe, comfortable and accurate examination, and if necessary, to provide you with whatever endoscopic treatment is indicated on the basis of our findings. |

| Watch a video From the American Gastroenterological Association |

What is upper endoscopy (also called EGD)? Upper endoscopy, or EGD, is an examination of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum (first section of the small intestine) performed by having you swallow an endoscope, usually while sedated. The endoscope is a long, thin, flexible and steerable tube, which is about the diameter of a small finger, and which passes easily through your mouth and throat structures following the natural food path.  Anatomy of the Digestive Tract (from Wikipedia) Anatomy of the Digestive Tract (from Wikipedia)What is an “open access” upper endoscopy? Many patients who are thinking about having an endoscopy performed prefer to avoid a traditional doctor’s office visit with the gastroenterologist prior to scheduling their procedure. Office visits provide an excellent opportunity to meet face-to-face with the doctor and talk in detail about the procedure, but they are also costly and time consuming, and require time away from work and other life activities that many people don’t wish to spare. In some cases the information that a patient and doctor needs to prepare for the safe and effective performance of an endoscopy can be obtained in other ways. Our “open access” program is designed with your easy access in mind. Our experienced registered nurses obtain your health history through a convenient telephone interview process at which time they will answer any questions you have about the planned procedure. The information you provide is entered into your permanent Digestive Health electronic medical record and forwarded to the physician for final review and approval in advance of your procedure date. The forms needed for registration at the time of your procedure are available here. We are able to offer open access services at this time on a limited case-by-case basis. In some instances an “open access” procedure is not the best option. Either the patient or the doctor may decide that an office visit before scheduling the procedure is the best way to go. Open access services are not a covered benefit of the Medicare program. |  |

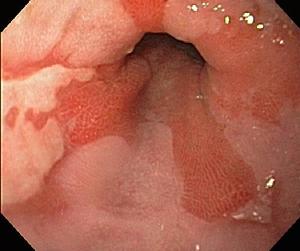

| Why is upper endoscopy performed? Upper endoscopy is performed to evaluate the esophagus, stomach and duodenum for a variety of disease processes which affect the interior lining of these organs, or block the normal passage of food and secretions through the upper intestines. Common diseases we evaluate and in some cases treat with upper endoscopy include gastroesophageal reflux disease, eosinophilic esophagitis, infections of the esophagus, Helicobacter pylori gastritis (stomach infection with the “ulcer bug”), ulcers of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum, and bleeding suspected to be arising from an upper intestinal source. What does the doctor see during an upper endoscopy? The following photographs obtained during examinations performed at the Southwest Endoscopy Center demonstrate normal findings |

| Middle section of the esophagus |

| Normal junction of the acid-sensitive esophagus (squamous) lining with the acid-resistant stomach (columnar) lining. The area of esophagus lining closest to the stomach is the area most frequently injured by acid in gastroesophageal reflux disease. |

| Middle section of the stomach, looking forward | Middle section of the stomach, looking backward (the endoscope is “retroflexed” in a U-shape, allowing us to look back at the upper stomach and the instrument entering the stomach from the esophagus) |

| Duodenum (first section of the small intestine) |

| Where should I schedule my procedure? (click for more information) Our doctors perform EGD in Durango at the Southwest Endoscopy Center. These are the only facilities in Southwest Colorado specializing the performance of gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures. What do I have to do to get ready for an upper endoscopy? You need to have an empty stomach. In most cases you may eat normally up until midnight on the day before your exam, after which you may continue clear liquids. No oral intake is permitted during the 4 hours before your arrival. What happens after I arrive and check in? You will need to check in at least 45 minutes before your actual planned EGD “start” time to allow for registration and admission to the Southwest Endoscopy Center, changing into a medical gown in a private preparation area, a preprocedure nursing assessment, placement of an IV line to allow administration of sedatives during your procedure, and a presedation physician assessment of your general health status and airway (mouth, throat and neck). Your family member or a friend is welcome to stay with you during this time. When all preprocedure preparations have been completed you will be taken by stretcher to the procedure room (where family members may not be with you), where a variety of monitoring devices (electrocardiographic skin electrodes, blood pressure cuff, finger oxygen sensor) will be placed. Either a nasal tube or an oxygen mask will be secured into position to provide oxygen during the procedure and allow for monitoring of exhaled carbon dioxide levels, if needed. A plastic mouth guard will also be positioned between your teeth. You may be asked to inhale an anesthetic (lidocaine) mist, or the nurse may spray this anesthetic into your throat. Once everything is ready and your gastroenterologist is in the room, the registered nurse assigned to your sedation and monitoring will administer a sedative under the doctor’s direction. Once you are asleep the doctor will pass the instrument over your tongue and into your esophagus. A second nurse or technician will assist the doctor. EGD usually takes about 10 minutes of actual instrument-in-the-body procedure time, though technically demanding procedures may occasionally take twice this long. Most patients sleep through their procedure and begin to awaken shortly after it is completed, prior to being taken by stretcher back to their preparation area, where they are monitored for a few minutes during recovery from sedation. While the procedure itself is typically painless, minor throat discomfort may be present on awakening. Most of our patients are ready to be discharged home about 20 minutes after the completion of their procedure, after reviewing their written procedure report and any necessary instructions with our nursing staff. I have a bad gag reflex and don’t see how I can actually swallow the instrument. Can the doctor keep me from choking, gagging or having trouble with my breathing during the procedure? Under procedural sedation the gag reflex is sufficiently suppressed to allow comfortable swallowing of the endoscope in almost every case. Patients generally have no recall of their procedure. The endoscope is of small diameter and does not interfere with your breathing when it is in place. I am worried about the idea of being sedated. How do you do this and how safe is it? (click for more information) How long is the instrument that goes inside me? What does it look like? (click for more information) How do you clean the instrument before you use it on me? (click for more information) How will I feel after its done? What can I do the rest of the day? Most of our patients feel a little bloated, relaxed, and relieved. Many are hungry and anxious to find some food. A temporary minor sore throat is not unusual, particularly if repeated instrumentation, such as is often the case with esophageal dilation, is also performed. We recommend that you eat a light meal to start with, and take it easy for a few hours. Many patients can then resume most of their activities right away, though driving should be restricted until the following day. You should expect to resume all of your normal activities the next day. What is reflux disease, and what does it look like during an endoscopy? Reflux disease, also known as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), is the cause of common heartburn. It may also cause trouble swallowing, chest pain, asthma, cough, hoarseness and a lump sensation in the throat called globus. Reflux disease is the result of excessive stomach fluid, which contains hydrochloric acid, bile and digestive enzymes, washing backward into the esophagus through a leaky valve at the bottom of the esophagus (incompetent lower esophageal sphincter). Endoscopy in patients with reflux disease may be normal. Often, a hiatal hernia is evident and the lower esophageal sphincter may appear not to close tightly. In some cases damage to the esophageal lining (erosive esophagitis, ulceration) due to acid-related injury is evident. Scar tissue may narrow the junction of the esophagus and stomach, causing a stricture. Chronic reflux injury may result in a change in the lower esophageal lining known as Barrett’s esophagus, which is important because of its potential to progress to cancer in a small percentage of cases. |

| These images show endoscopic photographs of a small hiatal hernia, looking forward at the diaphragmatic pinch (left), looking backward at the black endoscope entering from the esophagus (middle) and in a schematic representation (right). |

| Severe erosive esophagitis, with ulceration and early stricture formation. This photograph shows white ulcerated change affecting one-half the circumference of the esophageal wall at the level of the junction of the esophagus and a hiatal hernia of the stomach. Deformity of the wall is also evident, in association with narrowing of the junction |

| What is Barrett’s esophagus? How do I know if I have it? Why should I care? Barrett’s esophagus is a change in the lining (mucosa), usually due to reflux-related injury, from normal (squamous) to a more acid-resistant type of lining (columnar). This new lining appears endoscopically different and has particular characteristics (goblet cell metaplasia) under the microscope. While a Barrett’s type lining is less sensitive to acid injury, its presence is associated with a small future risk of esophageal cancer. The term dysplasia is used to describe changes in the Barrett’s lining which may reflect progression in the direction of cancer. Depending on the degree and extent of dysplasia your doctor may recommend more frequent monitoring or referral to a larger center for consideration of endoscopic or surgical treatments. |  |

| This photograph shows three GERD complications. Barrett’s esophagus is shown in the form of tongues of columnar lining extending upward into the normal esophageal squamous lining. Erosion of the squamous lining is seen in the 4 o’clock position at the tip of the Barrett’s tongue, and ulceration is seen between 8 o’clock and 10 o’clock extending above the margin of the photo. |

| I have trouble with food getting stuck when I swallow. What causes this? Can this problem be treated during my endoscopy? This symptom is called dysphagia (dis-fey-juh). It may result from several disease processes affecting the throat and esophagus. Upper endoscopy is most useful for evaluating and treating dysphagia arising in the esophagus, particularly when it is due to mechanical narrowing and partial blockage of the food path. The most common problems leading to solid food becoming stuck in the esophagus (after being “gulped down” but before passage into the stomach) are: 1. Strictures (scar tissue related narrowing) at the bottom of the esophagus due to acid-related injury of the esophageal lining in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) |

| These photographs show an ulcer (2 o’clock in the left photo) and stricture narrowing the esophageal opening at the junction of the stomach (seen as the poorly illuminated area straight ahead in the right photo), and precludes passage of the endoscope prior to dilation of the stricture. |

| 2. Narrowing of the upper-mid esophagus due to an allergic disease of the esophagus known as eosinophilic esophagitis (EE) |

| Narrow “ringed” esophagus characteristic of eosinophilic esophagitis |

| Patients with these two conditions usually describe intermittent episodes during which solid food (particularly meat) becomes stuck. In some instances the lodged food can be “washed down” with water after a few minutes. In other cases it is “vomited” or regurgitated back out. While the food is stuck it is difficult, even impossible, to swallow fluids around it. Even saliva will often not pass. This problem may require emergency medical attention for endoscopic removal of the impacted food. If episodic dysphagia is untreated it may progress to a daily problem limiting normal eating at every meal. Strictures due to GERD are most often treated with medications such as a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and dilation (enlargement of the narrowing), which is generally performed under sedation at the time of an endoscopy. A variety of instruments (balloon dilators, wire-guided thermoplastic dilators, tapered Maloney-type tungsten gel-filled silicone elastomer-cased bougies) may be used to enlarge a narrowing, depending on its shape and underlying cause. The goal is safe and gradual enlargement, avoiding serious injury (such as perforation), which may necessitate several visits over the course of weeks. Medication is usually continued long term to prevent stricture recurrence. Strictures due to EE may respond to dietary restriction or swallowed steroid treatment, but many adults presenting to our practice with EE-related dysphagia often need dilation. Other esophagus problems which may cause swallowing problems include infections, neuromuscular disorders which affect esophageal contractions or function of the esophageal sphincters, and cancer. |

| Can upper endoscopy cause complications? While EGD provides the important health benefits of accurate diagnosis and treatment of a variety of conditions, and allows for early dysplasia and cancer detection, there are potential risks of having the procedure performed, even when it is performed by an expert who is using proper technique and appropriate caution and care. Fortunately, for most patients the benefits easily outweigh the risks. It is important for you to feel that this is the right procedure for you before proceeding. Your primary care provider is an excellent resource for helping you with the decision to undergo EGD. Your Digestive Health gastroenterologist will review the risks, benefits, potential complications and alternatives to EGD with you prior to your procedure. If you are uncertain with regard to how you wish to proceed you should schedule an office visit to allow for more extensive discussion prior to making a decision about your procedure. Risks The most serious and important risks of EGD are the risk of missing something, the risk of a perforation (which is rare), the risk of bleeding and the risk of heart or lung problems related to sedation (which are very uncommon). EGD performed by an experienced gastroenterologist is the most accurate means of detecting abnormalities such as Barrett’s esophagus, ulcers and cancers in the upper GI tract, but no test is 100% accurate in this regard. In most cases, the risks of a serious complication of EGD are easily outweighed by the benefits. While events such as perforations are rare, they may occur in the context of a properly and carefully performed procedure. When complications do occur early diagnosis is important to an optimal outcome. If you are having any unexpected symptoms after an examination, such as increasing pain in your throat, neck, chest or abdomen, black or bloody bowel movements, vomiting, or fever, it is important to contact Digestive Health immediately and confer with your gastroenterologist or with the doctor who is providing coverage if your gastroenterologist is not available (see Emergencies). Perforations and similar serious injuries may require surgery for treatment. |

| I had an upper endoscopy this morning and now I have fever, chills and muscle aches. What is going on and what should I do? These symptoms are not expected and should be reported immediately to your physician. If you also have throat, neck, chest or abdominal pain or tenderness, an endoscopic complication such as perforation must be assumed to have occurred, until proven otherwise. Early diagnosis and treatment is key to achieving the best outcome. If you have no other symptoms your fever, chills and muscle aches may be due to the sedative administered for your procedure, particularly if you received propofol. The FDA and CDC have investigated clusters of propofol-associated fever from around the country, as discussed here. Evaluation and treatment for bacterial sepsis is recommended if this problem is suspected. FDA Alert of June 2007 I have a heart problem, and I need antibiotics before dental procedures and surgery. Do I need antibiotics for upper endoscopy? No. For decades we have administered IV or oral antibiotics prior to performing some upper endoscopic procedures, particularly those that involved dilation (stretching of a narrowing), but practices have changed. In April 2007 the American Heart Association updated its prior guidelines, which had been in place since 1997. The new guidelines state that “the administration of prophylactic antibiotics solely to prevent endocarditis is not recommended for patients who undergo GU or GI tract procedures, including diagnostic esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy.” The guidelines, which were published in the April 2007 edition of the journal Circulation, can be viewed here. I have an artificial joint. My orthopedic surgeon said I need antibiotics for upper endoscopy. Is this true? No. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), has concluded that antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with prosthetic joints is not recommended. If your surgeon advises you to take antibiotics anyway before and/or after your procedure, he or she may choose to provide you with a prescription for the agent of their choice. Click here to review the 2008 ASGE recommendations in their entirety. When do I get my results? Your full procedure report will be completed by your gastroenterologist and provided to you by our nursing staff, who will review your findings with you at the time of discharge. If any tissue (biopsies) was removed during your examination it will be forwarded to gastroenterology specific pathologists in Nashville, Tennessee for pathology review. Your gastroenterologist will contact you with further information about these specimens, typically in 7-14 days. A copy of these reports will be provided to your referring provider and to any other doctor or health care provider you choose, at your direction. We hope that this information helps you put the risks and benefits of upper endoscopy in perspective. Your gastroenterologist will be happy to talk with you further about this before your procedure. Please don’t hesitate to share your questions and concerns. |